From collection Jesup Library Maine Vertical File

Page 1

Page 2

Page 3

Page 4

Page 5

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

Search

results in pages

Metadata

Maine's First Buildings: The Architecture of Settlement, 1604-1700

MAINE'S FIRST BUILDINGS

The Architecture of Settlement, 1604-1700

By Robert L. Bradley, Ph.D.

Architectural Historian

Maine Historic Preservation Commission

MAINE'S FIRST BUILDINGS

he Architecture of Settlement, 1604-1700

Robert L. Bradley, Ph.D.

chitectural Historian

ine Historic Preservation Commission

This booklet was published in April, 1978 by the

Maine Historic Preservation Commission with private

funds provided by Citizens for Historic Preservation and

the Society for the Preservation of Historic Landmarks

in York County, Inc., matched by Federal funds provided

by the Commission through the Office of Archaeology

and Historic Preservation, Heritage Conservation and

Recreation Service, Department of the Interior.

EARLE G. SHETTLEWORTH, JR.

State Historic Preservation Officer

THE MAINE HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION was created by the 105th Legislature in 1971 to administer

the National Register Program in Maine. The Commission is responsible for conducting a statewide survey

of historic, architectural, and archaeological resources and the nomination of properties to the National Reg-

ister of Historic Places. In addition, the Commission administers a 50% matching Federal Grants-in-Aid

Program for the excavation of archaeological sites and the restoration of historic buildings.

CITIZENS FOR HISTORIC PRESERVATION is a state-wide historic preservation organization linking the efforts

of local preservation groups and historical societies. Citizens publishes a quarterly newsletter covering local,

state, and national preservation activities and since 1971 has sponsored annual conferences on preservation

issues, including Historic Districts, Buying Antique Houses, and Maine Archaeology.

THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF HISTORIC LANDMARKS IN YORK COUNTY, INC., is a non-profit organ-

ization dedicated to the preservation of York's colonial heritage. The Society maintains Jefferds Tavern,

the

George Marshall Store, the John Hancock Warehouse, the Elizabeth Perkins House, and the Old Schoolhouse

as historical museums. Landmarks such as the Old Burying Ground, Maude Muller Spring and Snowshoe

Rock are cared for by the Society.

Cover and Title Page: 19th-century photograph of the now

Booklet designed by Frank A. Beard, Historian

lost Junkins Garrison, York, C. 1707

Maine Historic Preservation Commission

Contents

Introduction

try to reconstruct a century of building in Maine

which is now all but vanished.

Survivals

From the moment that European settlers first

5

There are four principal sources of information in

splashed ashore in Maine early in the 17th century,

the study of Maine's 17th-century architecture:

buildings of various sorts were constructed to

Written Records

surviving structures or parts of structures, con-

7

meet their temporary as well as long-term needs.

temporary written records, contemporary drawings,

Those settlements which flourished quickly saw

and archaeological excavation of early remains.

Pictorial Records

9

the appearance of dwellings, storehouses, barns,

In approaching the subject from these four

mills, taverns, jails, churches, smithies-in short,

directions a remarkable amount of evidence can

Archaeological Evidence

12

all of the structures which frontier villages and

be collected to piece together a picture of Maine's

towns need to function as communities.

first buildings.

Final Notes

16

For several generations, from the 1620's to 1676,

early colonial Maine thrived. And then disaster

For Further Reading

16

struck. King Philip's War raged throughout New

England as the Indians made a futile effort to

turn back the English tide. Most of Maine's

settlements were completely destroyed or badly

damaged in this conflict and, what is even worse,

King Philip's War ushered in nearly a century

of bloody strife in Maine between the English and

Illustration Credits:

the allied French and Indians. Due to this strife

and the normal ravages of time, virtually no

"The Old Garrison" by Winslow Homer courtesy

trace of Maine's 17th-century architecture survives

of Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Smithsonian

above ground.

Institution's National Museum of Design.

This booklet is intended to be a companion to

"Piscataway River in New England" courtesy of

Frank A. Beard's 200 Years of Maine Housing:

the British Library Board.

A Guide for the House Watcher, Second Edition

(Augusta, Maine Historic Preservation Com-

Plan and Sketch, Turfrey's House, Saco Fort;

mission, 1977). Maine's architecture of the

Casco Bay Fort; and Pemaquid Barracks courtesy

settlement period is little understood, but through

of the Public Record Office, London, Crown

research more is being learned about it every

Copyright (C.O. 700, Maine 2, 11, 10.2).

year. This booklet will attempt to bridge the gap

in the study of architecture between the earliest

Spirit Pond Sod House artist's conception,

colonization of our State and the re-emergence

courtesy of Edward J. Lenik.

of prosperity in Maine in the 18th century. It will

3

4

"The Old Garrison" (Junkins Garrison), York, by Winslow Homer

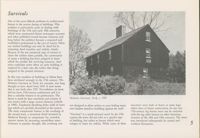

Survivals

One of the most difficult problems in architectural

history is the precise dating of buildings. This

problem is particularly acute in dealing with

buildings of the 17th and early 18th centuries,

which were constructed before newspaper accounts

and other published records became common; and

long before the architect became a respected and

established professional in the eyes of society. Often

our earliest buildings can only be dated by in-

terpreting deed transfers and stylistic details.

Because of the not unnatural urge of owners to

claim the earliest dates possible, the construction

of many a building has been assigned to times

which far predate the surviving structure. And

often confusion arises when an early building is

replaced by a later one, the earlier date being

assigned to the present structure.

In this way numbers of buildings in Maine have

been attributed wrongly to the 17th century. The

McIntire Garrison in York, for example, was long

thought to have dated from 1645. It now seems

that it was built after 1707. Nevertheless, its form

derives from 17th-century architecture and it is

thus a valuable witness to its predecessors. The

house is small by later standards and consists of

McIntire Garrison, York, C. 1707

two stories with a large central chimney (rebuilt

not designed to allow settlers to pour boiling water

structures were built of hewn or sawn logs,

in 1909). Clapboard sheathing hides walls of sawn

logs which are carefully dovetailed at the corners.

onto hapless attackers huddling against the wall!

others were of frame construction. In any case

The most conspicuous feature is the overhang of

17th-century log houses must not be confused

the second story, a structural detail invented in

"Garrison" is a much misused word. In the 17th

with the log cabin famous on other American

Medieval Europe to compensate for crowded,

century the term did not refer to a specific type

frontiers of the 18th and 19th centuries. The latter

narrow streets by increasing second-floor space.

of building, but rather to houses which were

was introduced subsequently by central and

5

Contrary to popular thought, this overhang was

refuges or bases for militia. While some of these

northern Europeans.

The Mitchell Garrison in Kittery, again probably

is misnamed, for it was built C. 1750 using parts

dating from the early 18th century, is also of log

of a late 17th century structure by that name.

construction. This building, however, barely quali-

And while the earliest part of the Elizabeth Per-

fies as a survivor since only its first story walls

kins House in York may have been built C. 1686,

remain. These have been dismantled and

it has been submerged by numerous later additions

moved to a safer location for reassembly and

and enlargements. However, the Fernald House

interpretation on the grounds of the Kittery His-

in Kittery, possibly dating from the 1690's, is a

torical and Naval Museum.

fine example of a one room deep, two-story frame

dwelling with large central chimney.

Viewing Maine's architectural survivals of the

17th century all too clearly indicates that they

hardly exist. One has to look at structures of the

Frost Garrison, Eliot, C. 1738

early 18th century to gain an impression of

earlier building types. In this regard Maine's

oldest standing Cape Cod style dwellings hint at

their humble ancestors of the 1600's-very small

one-story frame houses with loft overhead, a

chimney to one side and a single room downstairs.

This type of house was easily expandible into

the center-chimney cape SO typical of Maine's later

colonial period.

Fernald House, Kittery, C. 1700

never a dwelling (there was no chimney for heat

Mitchell Garrison, Kittery, detail, early

and cooking); rather, it functioned as a barn

18th-century

and was intended as a refuge in times of peril.

The Frost Garrison in Eliot is the most military

Although it dates from the 1730's, it might as well

in nature of these early log buildings in Maine.

have been built much earlier.

This large, barn-like structure is of one and a

half stories with an upper story overhang at the

The field-stone cell block of York's Old Gaol was

gabled ends of the building. Loopholes are cut into

once thought to date from 1653, but is now known

the first story log walls for musket fire. This was

to postdate 1720. The Storer Garrison in Wells

In 1633 John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay

ordered that no man there shall build his chimney

mentioned primitive shelters on the Maine coast:

Written Records

with wood, nor cover his house with thatch.

"News of the taking of Machias by the French.

Ironically, Dudley's own house burned in 1632,

Mr. Allerton of Plimouth, and some others, had

as reported by an eye-witness, Peter Force:

"

set up a trading wigwam there

,, And again

The hearth of the Hall chimney burning all night

An early but today anonymous visitor to New

in 1643: "Mr Vines landed his goods at Machias,

upon the principal beam. River sedge and rye

England wrote that Maine "will prove a very

and there set up a small wigwam

" We can

straw were used to thatch the roofs

" Thatch

flourishing place, and be replenished with many

only imagine what an English 'wigwam' amounted

was clearly the simplest and most easily used

fair towns and cities, it being a Province both

to, since it was never precisely defined, though

roofing material for many years for all buildings.

fruitful and pleasant". This was a good prediction,

the term was used repeatedly by early eye-witnesses.

Winthrop reported that a thatched barn burned

but towns and cities take time to build, requiring

Johnson wrote of New England in general in 1642,

in Salem in 1647 (already an aged structure by

efficient saw-mills and systematic brick-making.

The Lord hath been pleased to turn all the

them, presumably) and that the new Dorchester

The first European residents of Maine and New

wigwams, huts, and hovels the English dwelt

meeting-house of 1632 was thatched. Yet by 1646

England had to improvise shelter for a few

in at their first coming into orderly, fair, and

Winthrop implied that thatched roofs were a

well-built houses."

months or longer after arrival. These earliest

thing of the past when he noted that a certain

structures nowhere survive, were never pictorially

man "took up his lodging in a poor thatched

represented, and seldom leave buried remains

Occasionally we get glimpses of construction

house".

for the historical archaeologist to identify. However,

details of the first generation of buildings. At

they are liberally mentioned in contemporary

Plymouth, Bradford mentioned in 1623 the loss of

In general these roofs were of gabled form. For

journals and letters.

a "storehouse, which was wattled up with bowes,

example, Winthrop cited an unfortunate incident

in the withered leaves whereof ye fire was kindled."

in 1636: "One Mr. Glover of Dorchester, having

Edward Johnson, writing of the first settlement

The structure's walls were made of wattle and

laid sixty pounds of gunpowder in bags to dry in

of the Boston area in 1630, noted that "The first

daub which consisted of branches plastered

the end of his chimney, it took fire and some

station they took up was at Charles Towne, where

roughly with clay or mud. Winthrop, on the other

went up the chimney; other of it filled the room

they pitched some tents of Cloath, others built

hand, in 1632 noted a house near Boston "made

and passed out at a door into another room, and

them small Huts

In 1636 the first settlers of

all of clapboards".

blew up a gable end."

Concord, west of Boston, used a different type

of shelter, according to Johnson, "They burrow

Most, if not all, of early buildings in New England

Foundations clearly were of stone, not quarried

themselves in the Earth for their first shelter

were covered with thatched roofs. We know this

granite as in the 19th century, but rocks gathered

under some Hill-side, casting the Earth aloft upon

because of the frequent reporting of fires, many

from the fields. The difficulty of building sturdy

Timber; they make a smoakey fire against the

of which were incorrectly blamed on the roofing

foundation walls with rounded New England

Earth at the highest side." William Bradford,

material (actually, wooden chimneys were the

field-stone was wryly noted by Johnson in referring

writing of the first weeks at Plymouth in 1620,

chief cause). Fires became SO common in the

to two men trying to build à church in Salem

was unfortunately far less specific: "After they

early years that Thomas Dudley wrote in 1630 to

in 1629: "One of them began to build, but when

had provided a place for their goods, or comone

Lady Bridget, Countess of Lincoln, "For the

they saw all sorts of stones would not fit in the

store

[they] begune some small cottages for

prevention whereof in our new town [Cambridge],

building, as they supposed, the one betooke him to

their habitation, as time would admit."

intended this summer to be builded, we have

the Seas againe, and the other to till the Land."

7

Cellars are mentioned fairly frequently by early

This remarkable passage, although confusing in

The tents, pit-houses, wigwams, huts, and hovels

writers. This is hardly surprising, given the

places, tells us a great deal about a first generation

which served as improvised shelter for the first

New England climate where frost-free winter

building on the Maine coast which was designed

wave of settlers were soon replaced by far better,

storage and a cool larder in the summer are

as the headquarters of a successful fishing station.

yet still primitive, thatched cottages, often with

desirable. Increase Mather at Plymouth cited an

The building, 40 by 18 feet in ground dimensions,

dangerous wooden chimneys. In due course larger

Indian in 1621 "observing in one of the English

was equipped with a single large chimney

buildings with brick chimneys appeared. By the

Houses a kind of Cellar, where some Barrels of

apparently containing two very large back-to-back

mid-17th century Johnson's description of Boston

Powder were bestowed." And Winthrop wrote of

fireplaces. A wing was evidently used for storage

suggests the rapid advance of architecture in

a Boston house in 1648 equipped with a "well

and the hand-milling of corn. At least two major

New England within barely more than a generation

in the farther end of the cellar".

rooms were serviced by the fireplaces on the first

of the first settlement: "The chiefe Edifice of

floor, a kitchen-mess hall and an office ("steward

this City-like Towne is crowded on the Sea-banks,

Most eyewitness accounts of early 17th-century

room"). Upstairs was a large dormitory, another

and wharfed out with great industry and cost,

buildings in New England concern eastern

bedroom used for storage, and a small store room.

the buildings beautifull and large, some fairly

Massachusetts (e.g., Plymouth, Boston, Salem).

This was no wigwam.

set forth with Brick, Tile, Stone and Slate

"

However, one of the best contemporary references

to a dwelling of the period comes from the pen

Building contracts often contain information of

of John Winter, agent for Robert Trelawny on

value. For example, from the Biddeford Town

Richmond's Island, off Cape Elizabeth, in 1634:

Records come these 1686 specifications for a

"I have built a house heare. that is 40 foote

framed minister's house:

"

shingled

ye

in length and 18 foot broad within the sides,

sellare dug and stoned,

ye chimbes made of

besides the Chimnay, & the Chimnay is large with

brick".

an oven in each end of him We Can brew

& bake and boyle our Cyttell [kettle] all at once

While certain generalizations about the size,

in him with the helpe of another house that

shape, and construction materials of early 17th

I have built under the side of our house, [cellar?]

century buildings in Maine and New England can

where we sett our Ceves [sieves] & mill & morter

be made on the basis of contemporary written

In to breake our Corne & malt & to dres our

records, it is well to remember that in any period

meall in, & I have 2 Chambers [upstairs bedrooms]

there is great variation from the norm. A one-

in him, and all our men lies in on[e] of them, &

story house with a central brick chimney and a

every man hath his Close borded Cabbin [bunk]:

flat roof just nine feet high is hardly typical of

and I have Rome [room] Inough to make a

early colonial architecture as we understand it.

dozen Close borded Cabbins more, yf I have need

Yet Winthrop described just that in 1646: "A

of them, & in the other Chamber I have Rome

most dreadful tempest at northeast with wind and

Inough to put the ships sail into and I have

rain, in which the lady Moodye her house at

a store house in him

& underneath I have a

Salem, being but one story in height, and a flat

Citchen for our men to eat and drink in, & a

roof with a brick chimney in the midst, had the

steward Rome

, and every one of these romes

roof taken off

"

8

ar Close with loockes & keyes vnto them."

a detailed drawing survives showing an elaborate

Pictorial Records

village within a massive fortification of irregular

star form. This drawing by a John Hunt is dated

October 8, 1607; and since it is known that the

Because virtually no 17th-century buildings survive

site of the settlement was not selected until August

in Maine and because written accounts leave

18th, many details in the drawing must be

much to the imagination, early sketches and

critically viewed. Cannon of various calibers

paintings depicting buildings of the settlement

belch smoke from most of the bastions, and the

period are extremely valuable as a source of

land and water entrances are surmounted by

information.

elaborate turreted gates of medieval form. The

buildings shown within Fort St. George (as it

The two earliest documented European attempts

was named) include a chapel with a tower at one

at colonizing the Maine coast have left us the

end, along with more than a dozen dwellings,

most dramatic graphic records of the 17th-century,

storehouses, and workshops. There is more uni-

Ironically, each enterprise failed within a year,

St. Croix Colony, 1604

formity here than at St. Croix. All the buildings

and it seems likely that the pictorial record of

are one story tall and all have gabled roofs with

each is either an exaggeration of what actually

stories; to a pair of handsome residences (R),

central or end chimneys. Yet it is hardly credible

was built, or a 'blueprint' for what was planned

consisting of attached two-story buildings with

that such a community could have been built in

but only partially completed.

central chimneys and hipped roofs. Whether

just over seven weeks.

prefabricated in France or built with local

In 1604 France established a colony on St. Croix

materials, it is known that these buildings were

While the St. Croix and Fort St. George drawings

Island (Dochet Island) off of the modern Calais.

of frame construction. Some at least were dis-

are both suspect in detail, they nevertheless give

The unfortunate combination of an exposed site,

mantled and shipped in 1605 to the new site at

a good impression of the architecture of the first

a very severe winter, starvation, and disease

Port Royal, Nova Scotia. While there is no reason

French and English settlements. And even if they

decimated the settlers, and in the following sum-

to believe that all of these buildings were not

were works of fiction, they would show, as in a

mer the colony was removed to Nova Scotia. The

constructed, Champlain's drawing almost certainly

blueprint, the intentions of the earliest colonists.

great explorer Samuel de Champlain was a

exaggerates their size and complexity. Archaeologi-

participant in the effort, and his detailed drawing

cal excavations may yet resolve the issue.

From the mid-17th century comes a map signed

of the settlement in the St. Croix River was

"I.S." of "The Piscataway River in New England".

published in 1613. This charming drawing shows

In the summer of 1607 a party of Englishmen

This depicts many individual houses dotting the

buildings and gardens at the northern end of

under the leadership of Sir John Popham estab-

coast and river banks of what are now Kittery

the island. These range in type from a kitchen

lished a settlement near the mouth of the Kennebec

and York. Practically all of the buildings shown

(I) of one story with a flat or shed type roof; to

River. The site of the Popham Colony has for

are one-story frame dwellings with central chimneys

quarters and shops for smiths and carpenters

generations been disputed, but it may lie on the

and gable roofs. Occasionally a half-story facade

(E, F) consisting of gable-roofed row-houses of

west side of the river at Atkins Bay in Phippsburg.

dormer is present along with a low gable-roofed

one and a half stories; to the residence of the

Like the St. Croix settlement, this colony was

ell. No other source SO graphically reflects how

settlement's leader, the Sieur de Monts (A), a

defeated within a year of its foundation by poor

humble were most buildings in Maine even by

small hip-roofed dwelling of one and a half

morale and a severe winter. And as with St. Croix,

about 1660.

9

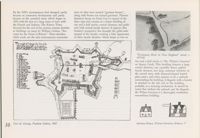

By the 1690's circumstances had changed, partly

tions of what were termed "garrison houses",

because of continued development and partly

along with houses not termed garrisons. Thomas

because of the unsettled times which began in

Spinney's house on Great Cove is typical of the

1676 with the first of a long series of wars with

latter type and consists of a frame dwelling of

the French and Indians. The Kittery Town

one and a half stories, central chimney, and gable

Records for the end of the century contain sketches

roof with central facade dormer. It appears that

of buildings on maps by William Godsoe, "Sur-

Godsoe's perspective has brought the gable-ends

veyor for the Town of Kittery". These sketches,

around to the facade, creating a false appearance

while crude, are the only contemporary representa-

of three facade dormers. Much larger at two or

"Piscataway River in New England" detail, C.

1655-60

two and a half stories is "Mr. Wilson's Garrison"

on Spruce Creek. This dwelling features a large

central chimney, one (possibly three) gabled

facade dormers, two large casement windows in

the second story with diamond-shaped leaded

glass panes, and what appears to be a palisade

surrounding the building. A flagpole with a banner

is attached to the left end of the building,

probably as a warning mechanism. It should be

Occudental.

noted that without the palisade and the flagpole,

the Wilson Garrison is a thoroughly residential,

non-military building.

10

Fort St. George, Popham Colony, 1607

Spinney House, Wilson Garrison, Kittery,

In 1699 the great English military engineer, Col.

additional sleeping quarters. This was frontier

Redknap's plan and perspective drawing shows

Wolfgang W. Romer, drew precise plans of a

architecture of a basic nature. Yet it hardly differs

barracks ranged along one of the sides of the

number of existing forts on the Maine coast.

from the smallest and earliest surviving 'capes' of

curtain-wall. These were to be covered with a flat

One of these was Saco Fort, built in 1693 and

the early to mid-18th century.

roof rather than the more common shed roof.

commanded by Capt. John Turfrey, among others.

Heat was to be provided by at least one pair of

Romer's plan and sketch of the installation shows

back-to-back corner fireplaces. Paired casement

Turfrey's house outside of the fort. This building

windows and doors at regular intervals were to

was of frame construction, one story high, with

give light and access to the various vaulted com-

a gabled roof. A small northern extension was

partments. While strictly military in character,

covered with a shed type roof. In plan the house

this drawing depicts living quarters which were

from south to north consisted of a major room

Casco Bay Fort, detail, 1705

planned for the Maine coast shortly after the close

and a smaller room divided by a partition and

of the 17th century.

back-to-back fireplaces. A third room beyond

Casco Bay Fort was built near the mouth of the

was unheated, as was the shed at the northern

Presumpscot River in Falmouth by Col. Romer in

end. There may have been a loft overhead for

1700 to replace Fort Loyal (located in present-

day Portland and destroyed by the French and

Indians in 1690). In 1705 Casco Bay Fort was

greatly enlarged by Col. J. Redknap, another

military engineer. Redknap's plan of the old and

new forts survives and shows the internal buildings

in plan and section. These include storehouses

and barracks. They were frame buildings with

posts set directly into the ground supported by

buried rock footings. Both gable and shed type

roofs were used.

Pemaquid was first established as a settlement

about 1625 and became England's northeastern-

most bulwark against French Acadia. As such,

it was provided with a wooden fort in 1677

(destroyed by the French and Indians in 1689)

and a stone fort in 1692 (destroyed by the same

alliance in 1696). The loss of the second fort was

a strategic blow to English Maine, and in 1699

Col Romer drew detailed plans of the lost fort

and a much larger one planned to replace it.

Plan and Sketch, Turfrey's House, Saco Fort,

In 1705 Col. Redknap did the same. Although

1699

neither of the proposed replacements was built,

Pemaquid Barracks, 1705

11

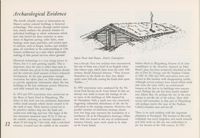

Archaeological Evidence

The fourth valuable source of information on

Maine's earliest colonial buildings is historical

archaeology. This science, through careful excava-

tion, closely analyzes the physical remains of

individual buildings or whole settlements which

have lain buried for three centuries or more.

Areas of flagstone paving, cellar holes, stone

footings, stone steps, post-holes, and certain types

of artifacts, such as hinges, latches, and window

glass, all contribute to the understanding of 17th-

century architecture in a state where practically

nothing of that period survives above ground.

Spirit Pond Sod House, Artist's Conception

Historical archaeology is a very young science in

Maine, but it is now growing rapidly. This is

was a fire-pit. Very few artifacts were encountered,

Sabino Head in Phippsburg, because of its close

important, since the state is richer than most in

but one of them was a bowl of an English white

resemblance to the shoreline depicted on John

early colonial sites, given its low population density

clay tobacco pipe which dates from the early 17th

Hunt's plan, has been tentatively identified as the

and the relatively small amount of heavy industrial

century. Recall Edmund Johnson: "They burrow

site of Fort St. George and the Popham Colony

development. In the past generation enough

themselves in the Earth for their first shelter

of 1607. In 1962 and 1964 excavations were con-

excavation has taken place on 17th-century sites

under some Hill-side, casting the Earth aloft upon

ducted at this location with disappointing results.

to provide significant information about the lost

Timber

Although several artifacts were found which could

buildings of the first settlement period. However,

date from the early 1600's, no architectural

such field research has only begun.

In 1950 excavations were conducted by the Na-

features of the fort or its buildings were encoun-

tional Park Service on St. Croix Island. In this, an

tered. Perhaps the site has been mostly washed

In 1973 and 1974 excavations were carried out on

attempt was made to locate the footings of one

into Atkins Bay. Or perhaps the site of the exca-

the Shore of Spirit Pond in Phippsburg. The

or more of the buildings of 1604 depicted by

vations is not the site of the colony. More field

object of this work was two prominent depressions

de Champlain. Only a small area was uncovered,

survey and excavation in that part of Phippsburg

within small mounds which clearly seemed to be

suggesting substantial disturbance of the site by

will perhaps resolve the issue of the Popham

the work of man. These features turned out to

cultivation in the ensuing centuries. However, two

Colony's location once and for all.

be primitive shelters dug into the bank and

parallel stretches of field-stone footings almost

roofed over with logs and turf. The larger of the

sixty feet long may represent the foundation of a

There is no such problem with the important

two structures measured some 32 by 21 feet on

storehouse (B, in de Champlain's drawing). Other-

plantation at Pemaquid. The location of this early

the outside, enclosing an internal chamber of

wise little was found in the way of architectural

settlement was never forgotten, and much research

12

about 21 feet long by 7 feet wide, with a rock-lined

features. Clearly, more work needs to be done

and field work on this site was undertaken in

entrance. Located near the middle of the chamber

on St. Croix Island.

the last decades of the 19th century. In 1923

further excavations were conducted, but the princi-

before Indians descended on the abandoned

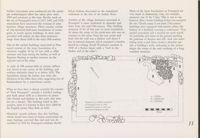

Many of the stone foundations at Pemaquid are

pal archaeological effort has taken place since

settlement in the first of the Indian Wars.

very small in dimensions. One, for example,

1965 and continues at this time. Besides work on

measures just 11 by 7 feet. This is not to say,

the site of Pemaquid's forts of 1677, 1692, and 1729,

Another of the village structures excavated at

however, that a frame building of that size occupied

excavations have uncovered the remains of some

Pemaquid is more residential in character and

the site. Clearly many if not most 17th-century

fourteen village structures. These remains consist

dates from the mid-17th-century. This dwelling

buildings were equipped with partial cellars, the

of clay-mortared field-stone foundations of rectan-

measures 16 by 18 feet over its stone foundation.

balance of a building covering a crawl-space. Very

gular or nearly square buildings, in most cases

At about the center of the north-west side was an

careful excavation and a trained eye must search

provided with cellars. In date these structures

entrance to the cellar. Near the east corner and

for post-holes and stains in the ground marking

range from about 1630 to the early 18th century.

built into the wall was a shallow well about 3

the positions of sleepers and sills. And rain water

feet in internal diameter which contained a wooden

falling from a roof often creates a drip-line out-

One of the earliest buildings uncovered at Pem-

barrell as a lining. Recall Winthrop's mention in

side a building's walls, indicating to the archae-

aquid consists of the stone foundation of a

1648 of a Boston house with a "well in the

ologist the extent of the roof overhang of a long-

structure roughly 40 by 24 feet with a cellar

farther end of the cellar".

vanished structure.

entrance and steps facing the harbor, as well as

flagstone flooring at another entrance on the

opposite end of the cellar.

A cache of 108 cannon balls of various calibers

B

was found in one corner of the building, and

artifacts definitely dated it to before 1676. The

foundation facing the harbor was twice the

B

thickness of the other three sides, suggesting fear of

bombardment by a water-borne enemy.

What we have here is almost certainly the remains

of "Fort Pemaquid", actually a fortified trading

post built about 1630 as a deterrent to piracy

A - STEPS

(the French and Indians at this early date were

B BEDROCK

not yet a threat). The building failed in this

Remains of a fortified storehouse

PAVING

purpose, since it is known to have been rifled by

at Pemaquid, built in 1630,

the English pirate, Dixy Bull, in 1632.

attacked by pirates n 1632 and

destroyed by Indians in 1676.

10 feet

Historical records indicate that this building,

which would have been of frame construction on

stone footings, survived this raid and was de-

molished in 1676 by Pemaquid residents shortly

13

A

A entrance

B well

10 feet

14

Dwelling, Pemaquid, C. 1650

Since 1970 archaeological excavations have been

conducted on the site of the Clarke and Lake

Company on Arrowsic Island. This remarkable

industrial complex which included a fort, a trading

post, mills, foundry, and shipyard, was established

by two prominent Boston merchants in 1654. In

1676, as with other English settlements, it was

attacked and destroyed by the Indians. The in-

vestigation of this site has concentrated on one

of at least half a dozen structures.

B

Excavation of this building, while not finished,

has revealed more about the structure than

everything written about the company's physical

plant and operations. In all likelihood, it was the

trading post or headquarters. What has been

uncovered is the stone footings of a building

rectangular in plan, some 40 feet long and 15

feet wide. The northern end of the structure is

occupied by a stone chimney base and the stone-

paved hearth of an enormous fireplace which was

12 feet wide and which faced south. Traces of

sills and planks indicate that the frame building

had a wooden ground floor. A lock and key found

near the east end of the hearth suggest the position

of an entrance. Fragments of window glass were

not concentrated sufficiently to indicate fenestration,

although there was a major grouping near the

center of the east wall. Attached to the north-east

corner is a projection about 5 feet wide which runs

northward. This may represent an enclosed entrance

or an attached shed. Its northern terminus has

yet to be uncovered.

A curious feature lies to the west of the building.

This consists of what may have been a narrow

paved alley, only 2 to 3 feet wide, between the

west wall of the building and another wall farther

to the west. Future excavation should determine

the exact nature of this feature.

The tools of archaeology have only begun to be

used at the Clarke and Lake Company Site, and

even at Pemaquid much remains to be done.

Whole villages, such as Sheepscot Farms, await

excavation. In the coming decades historical archae-

ology should contribute invaluable data to the

study of Maine's 17th-century architecture.

10 feet

of

Residence, Arrowsic, 1654

15

Final Notes

For Further Reading

The Trelawny Papers, ed. by James P. Baxter

(Portland, 1884).

Winthrop, John, History of New England

Beware the Mainer who claims a home of the

SURVIVALS:

(Boston, 1825-26, 1853).

17th century. It is not so. To study the architecture

Candee, Richard M., "The Architecture of

of the state's first European settlements one must

Maine's Settlement: Vernacular Architecture to

examine early 18th-century buildings which reflect

About 1720" in Maine Forms of American

ARCHAEOLOGY:

earlier construction methods. Contemporary written

Architecture, ed. by Deborah Thompson,

Camp, Helen B., Archaeological Excavations

accounts and descriptions are invaluable. And

(Waterville, 1976).

at Pemaquid, Maine, 1965 - 1974 (Augusta,

archaeology is providing a fourth primary source

Cummings, Abbott Lowell, Architecture in

of information. Archival and field research is

1975).

Early New England (Sturbridge, Mass., re-

Hadlock, Wendell S., "Recent Excavations at

producing new data every year. As this research

vised edition, 1974).

DeMonts' Colony, St. Croix Island, Maine",

proceeds, our view of Maine's earliest buildings

Myers, Denys Peter, Maine Catalog, Historic

is becoming clearer and clearer. This is important

American Buildings Survey (Augusta, 1975),

Old-Time New England, XLIV, 4 (1954),

92-99.

if we are to understand the entire history and

1-13.

evolution of Maine's architecture, an evolution

Lane, Gardner, An Archaeological Report on

Excavations Carried out at Sabino Head in

now covering nearly four centuries.

Popham Beach, Maine, the Site of Fort St.

CONTEMPORARY ACCOUNTS:

George, 1607 - 1608 A.D. (unpublished type-

Bradford, William, History of Plimoth Plan-

script, Bureau of Parks & Recreation, Augusta,

tation (Boston, 1901).

1966).

Force, Peter, Tracts and Other Papers Relating

Leamon, James, Archaeological Report on the

Principally to the Origin, Settlement and Pro-

Clarke and Lake Settlement, Arrowsic, Maine

gress of the Colonies in North America (Wash-

for 1970 - 1975 (unpublished typescript, De-

ington, D. C., 1836-46).

partment of History, Bates College, Lewiston).

Johnson, Edward, Wonder-Working Provi-

Lenik, Edward J., The Spirit Pond Sod

dence, a History of New England, 1628

House (Milford, N. H., 1973).

1651, ed. by J. Franklin Jameson (New York,

1910).

Jones, Augustine, The Life and Work of Tho-

mas Dudley, the Second Governor of Massa-

chusetts (Boston, 1899).

Mather, Increase, A Relation of the Troubles

which have hapned in New-England, By reason

of the Indians there From the Year 1614 to the

Year 1675, ed. by Samuel Drake (Albany,

N. Y., 1864).

Maine Historic Preservation Commission Publications

This booklet is one of a continuing series of publications documenting Maine's historic,

architectural, and archaeological heritage. Sponsored by the Maine Historic Preservation

Commission, each study may be ordered free of charge on a one per person basis by

sending 50c for postage and handling to the Maine Historic Preservation Commission,

242 State Street, Augusta, Maine 04333.

Beard, Frank A., 200 Years of Maine Housing: A Guide for the House Watcher (1976).

Mundy, James H. and Shettleworth, Earle G., Jr., The Flight of the Grand Eagle: Charles

G. Bryant, Maine Architect and Adventurer (1977).

Bradley, Robert L., Maine's First Buildings: The Architecture of Settlement, 1604-

1700 (1978).